Authors: Ian Bhatia, Tej Thambi

Posted: January 2024

Intro

This blog details our preliminary work addressing the following research question: how does awe manifest in psychedelic-assisted therapy (PAT) and what are its observable characteristics?

In recent years, PAT been established as an effective treatment for depression for people with advanced illness (Haikazian et al., 2023). The well-established construct of the “Mystical Experience” (Pahnke & Richards, 1966) is thought to be a potential mediator of the benefits of PAT (Baker et al., 2023), with signs that awe is a necessary component of this experience (see AWE-S questionnaire (Yaden et al., 2018) and the Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MacLean et al., 2012)). Awe can be understood as a powerful, distinct emotion that we experience in response to profound phenomena that challenge our understanding of the world (Keltner & Haidt, 2003). And yet, little work has been done to understand what awe looks like in the PAT encounter. We aim to identify characteristics of the manifestations of awe in the PAT context and develop methods for automating detection of “moments of awe” which can be used in future research and practice relating to PAT.

Our data

We are working with data from a Phase 2 clinical trial of psilocybin-assisted therapy for cancer patients with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). The study began with preparation sessions where patients met with their therapists to prepare for the dosing session and establish a therapeutic alliance. During dosing, patients received 25 mg of synthetic psilocybin and were supported by their therapist throughout the duration of drug action. One day later and one week later, patients attended integration sessions, during which they met with their therapists to reflect on their experience and integrate it into their daily life.

Approach

A previous paper from our lab (Gramling et al., 2023) coded four patients’ dosing day videos (approx. 8hrs each) for moments of “human connection” with various non–exclusive subtypes, one of which was awe/wonder. Working on the same set of four videos, for the present project we (two undergraduate research assistants) coded for awe being expressed by the participants. It is important to note here that we are distinguishing between awe and wonder, which the previous paper did not do. Awe is thought to be more about observing something profound, while wonder involves more of an effort to “understand” profound phenomena (Darbor et al., 2015).

In coding for awe, two coders watched and listened to the dosing videos and took note of moments which seemed to include expressions of awe, as defined by Keltner. This meant that we were primarily focused on observing vastness and a need for accommodation. Within this method of coding for awe, we made note of the features of awe that were present in each moment. These features included ones put forth by Keltner (e.g. time alterations, self diminishment) as well as ones that we identified as relevant and common to our data set (ineffability, meaning making).

Preliminary findings

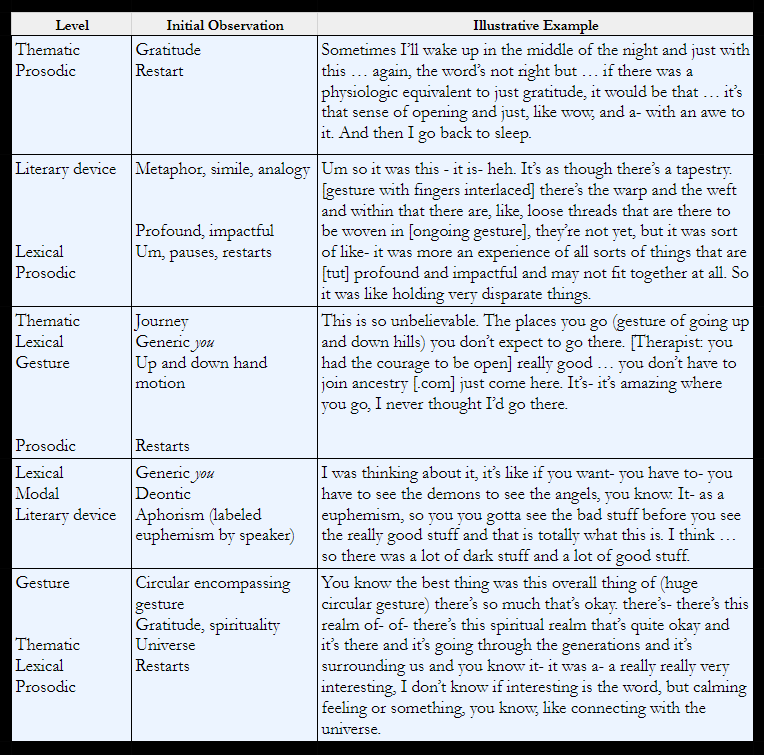

We have noted several lexical and prosodic features that seem to accompany the expression of awe. On the conceptual/thematic level, people talked about time, space, nature, gratitude, spirituality, and journeys. People also often used literary devices such as metaphor, simile, analogy, and aphorism in their expressions of awe and awe-inspiring experiences. They also often used the deontic modality (e.g. should, have to, must, etc.). On the level of lexical items, the following often appeared: Primordial, profound, impactful, powerful, unbelievable, beautiful, universe, spiritual, intense, superpowers, undeniable, oneness, amazing, awesome. Another interesting lexical feature of these moments of awe is the generic you, which seems to be used during the process of meaning making and extracting lessons from the experience, and often occurs in tandem with the deontic modality (e.g. “you have to ___”). At the level of prosody, we observed lower rate of speech and higher rates of pauses and disfluencies (e.g. restarts, “uh”, “um”) than during non-awe moments during the dosing day. Also worth noting are the irregular hand gestures denoting grandiosity or internality that often accompanied verbalizations of awe. We have included several examples in the table below.

Interpretation of findings

Our interpretation of these findings is that (1) the lexical items and thematic elements are in line with both awe and the mystical experience as they are often described, and that (2) the prosodic and literary device elements indicate a difficulty to express such an experience. This difficulty is often referred to as ineffability, which we believe to be a main feature of awe. It seems that the disfluencies, lower rate of speech, and pauses are indicative of the individual’s (perhaps futile) attempts to verbalize a profound experience for which there may not be sufficient linguistic tools. Furthermore, we believe that the identified prosodic features are a way for the participant to communicate incommunicability. These interpretations are in line with previous findings which identified ineffability as a theme of patient speech relating to psilocybin-assisted therapy (Belser et al., 2017). We hope to elaborate on the importance of some features identified by Belser et al., as well as add to the list of features of ineffability. Our claim is that ineffability has robust and varied thematic, lexical, and prosodic features including the “ineffability just,” identified in our lab (Manetta & Bhatia, in press).

Questions of empiricism

When attempting to quantify and qualify an intimate and profound personal experience such as awe (especially in a PAT context), there are questions of the extent to which we can draw a connection between the experience of awe and the expression of awe. During the dosing day, many individuals may have experienced profound moments of awe yet remained silent for a prolonged period. Furthermore, expressions of awe might occur during the experience of awe, or they might occur afterwards, being indicative of the patient’s attempt to make sense of such an experience. This “making sense” might fall more into the category of wonder rather than awe, seeing as wonder is thought to have more to do with making sense of an experience while awe is about the experience itself (Darbor et al., 2015). The question of how to separate awe from wonder is one that we will carry with us in future work.

Next Steps

As mentioned earlier, these preliminary findings are based on the work of two coders with a relatively unstructured method of coding for awe. While useful for establishing early approaches to operationalizing a coding system, our next steps will require more observations, more diversity of participants, cultures and contexts, more coder perspectives and, ultimately, more uniform coding definitions to guide the identification of awe expression.

References

Baker, K. M., Ulrich, C. M., & Meghani, S. H. (2023). An integrative review of measures of spirituality in experimental studies of psilocybin in serious illness populations. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®, 40(11), 1261–1270. https://doi.org/10.1177/10499091221147700

Belser, A. B., Agin-Liebes, G., Swift, T. C., Terrana, S., Devenot, N., Friedman, H. L., Guss, J., Bossis, A., & Ross, S. (2017). Patient experiences of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 57(4), 354–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167817706884

Darbor, K. E., Lench, H. C., Davis, W. E., & Hicks, J. A. (2015). Experiencing versus contemplating: Language use during descriptions of awe and wonder. Cognition and Emotion, 30(6), 1188–1196. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2015.1042836

Gramling, R., Bennett, E., Curtis, K., Richards, W., Rizzo, D. M., Arnoldy, F., Hegg, L., Porter, J., Honstein, H., Pratt, S., Tarbi, E., Reblin, M., Thambi, P., & Agrawal, M. (2023). Developing a direct observation measure of therapeutic connection in psilocybin-assisted therapy: A feasibility study. Journal of Palliative Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2023.0189

Haikazian, S., Chen-Li, D. C. J., Johnson, D. E., Fancy, F., Levinta, A., Husain, M. I., Mansur, R. B., McIntyre, R. S., & Rosenblat, J. D. (2023). Psilocybin-assisted therapy for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 329, 115531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115531

Keltner, D., & Haidt, J. (2003). Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cognition and Emotion, 17(2), 297–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930302297

MacLean, K. A., Leoutsakos, J. S., Johnson, M. W., & Griffiths, R. R. (2012). Factor analysis of the mystical experience questionnaire: A study of experiences occasioned by the hallucinogen psilocybin. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 51(4), 721–737. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5906.2012.01685.x

Manetta, E., & Bhatia, I. (in press). “It was just so hard”: ineffability just as a mixed expressive. Glossa: A Journal of General Linguistics.

Pahnke, W. N., & Richards, W. A. (1966). Implications of LSD and experimental mysticism. Journal of Religion and Health, 5(3), 175–208. https://doi.org/10.2307/27504799

Yaden, D. B., Kaufman, S. B., Hyde, E., Chirico, A., Gaggioli, A., Zhang, J. W., & Keltner, D. (2018). The development of the Awe Experience Scale (AWE-S): A multifactorial measure for a complex emotion. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(4), 474–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2018.1484940