Authors: Cailin Gramling & Robert Gramling

Posted: April 2020

Introduction

Within serious illness conversation, the feature of silence can act as a communicative and data rich moment. As established in our previously published paper (Durieux et al. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2018), some types of pauses represent moments of human connection. We identified these moments as ‘Connectional Silences’ through the conceptual taxonomies by Back et al and Bartels et al. From these we defined three categories to be Invitational, Emotional, and Compassionate. The first, Invitational, refers to a moment where space is left for contemplation of one’s response. The second two, Emotional and Compassionate, are founded around moments of gravity where we define gravity to be an expression of emotion whose experience is unpleasant. The latter is differentiated from the former through the second participant in the exchange acknowledging the moment of gravity.

These Connectional Silences present as an opportunity for patients, families, and clinicians to process and contemplate emotion and new information within conversations, as well as allowing for a potential shift in conversation to explore what matters most to the patient (https://vermontconversationlab.com/a-case-study-of-conversation-surrounding-a-compassionate-silence/). Little is known about what effect, if any, these Connectional Silences have on communication quality. Here, we present preliminary findings about the association between the presence of Connectional Silence in palliative care consultations and improvement in patient ratings of healthcare communication quality.

Methods

The Palliative Care Communication Research Initiative (Gramling et al., BMC Palliative Care. 2015) is a multi-site cohort study of inpatient consultations involving 54 palliative care specialists and 240 people who have advanced cancer. All participants completed an 18-item questionnaire before the consultation. Nine people were discharged, died or changed their mind about having a palliative care consultation soon after enrollment. The remaining 231 consultations were audio-recorded. Ninety one percent (n=210) of participants completed a 2-item questionnaire the day following the consultation. Both the pre and post consultation questionnaire asked, “[Over the past two days] [Today], how much to you feel heard and understood by the doctors, nurses, and hospital staff?”. Response options included, “Completely”, “Quite a Bit”, “Moderately”, “Somewhat”, or “Not at All”. This “Heard & Understood” Item (Gramling et al. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2015; Ingersoll et al. Pateint Education and Counseling. 2016) is currently in development as one of two core quality indicators for palliative care practice (https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/macra/).

Following established methods developed by our team (Durieux et al. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2018), we double coded all two-second pauses arising in the first fourth (n=66/231) of the PCCRI conversations to distinquish Connectional Silences from other pauses.

Preliminary Results

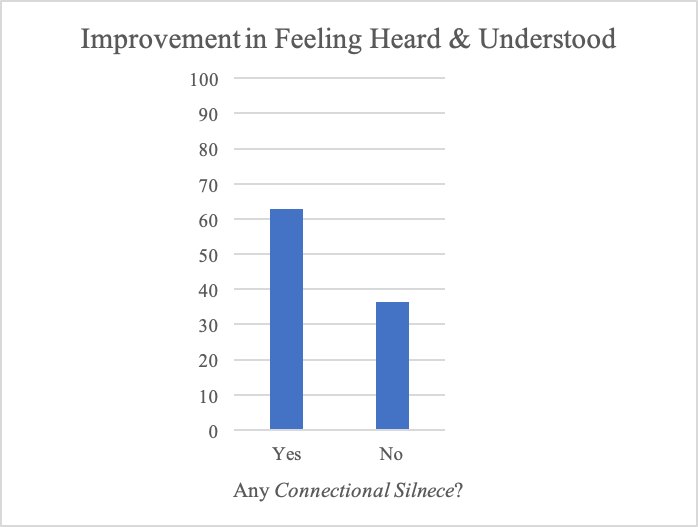

Forty-six participants (70%) did not feel Completely” heard and understood prior to the palliative care consultation. Fifty-seven percent of these participants (n=26/46) reported improvement in feeling Heard & Understood the day following the consultation. Thirty-five (76%) experienced at least one Connectional Silence during the palliative care consultation.

The presence of at least one Connectional Silence was strongly associated with improvement in patient ratings of feeling Heard & Understood (OR= 3.0; 95% CI= 0.7, 12.1). Accounting for the duration of the conversation, the presence of a Connectional Silence was associated with more than four times the odds of improvement (OR=4.4; 95% CI=0.9, 20.8). Adjusting for age, gender, race and self-rated quality of life does not substantially affect this estimate (ORadj= 4.1; 95% CI=0.8, 20.9).

Preliminary Conclusions

The presence of at least one Connectional Silence during palliative care consultation may have a substantial association with pre-post improvement in feeling Heard and Understood among people with advanced cancer being cared for in the hospital environment.