Authors: Jack Straton & Robert Gramling

Posted: March 2020

Fear, sadness and anger are commonly expressed during palliative care consultations (Alexander SC et. al. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2015). Recently, we discovered that features of serious illness conversations organize into observable arcs in the shared narrative (Ross LA et. al. Patient, Education and Counseling. 2020). Little, however, is known about the typical trajectory of fear, sadness and anger expression in these conversational stories and whether these arcs differ by the type of emotion. Better empirical understanding of the epidemiology of serious illness conversations is essential to guide effective quality measurement, system re-design, and communication training.

The Palliative Care Communication Research Initiative (Gramling R et. al., BMC Palliative Care. 2015) is a multi-site cohort study of inpatient consultations involving 54 palliative care specialists and 240 people who have advanced cancer. Nine participants died, discharged, withdrew or declined having a palliative care consultation before a study conversation was recorded. One conversation happened exclusively over telephone and coders could not validly assess patient/family expression of emotion. The analyses in this report use the data obtained during the remaining 230 conversations from each patients’ initial visit with the palliative care specialists.

Expert coders evaluated each speaker turn for the presence of fear, sadness and anger using established methods that consider both lexicon and prosody of speech (Alexander et al. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2015). We used Natural Language Processing to divide conversations into deciles of narrative time based on word counts. For each conversation, we identified (1) the decile when fear, sadness and anger were first expressed and (2) the distribution of fear, sadness or anger over narrative time. For each decile, we calculate the relative proportion of first expressions occurring in that decile and the relative proportion of expression counts in that decile (the denominator used to calculate these proportions was the number of conversations with at least one expression of the specific emotion).

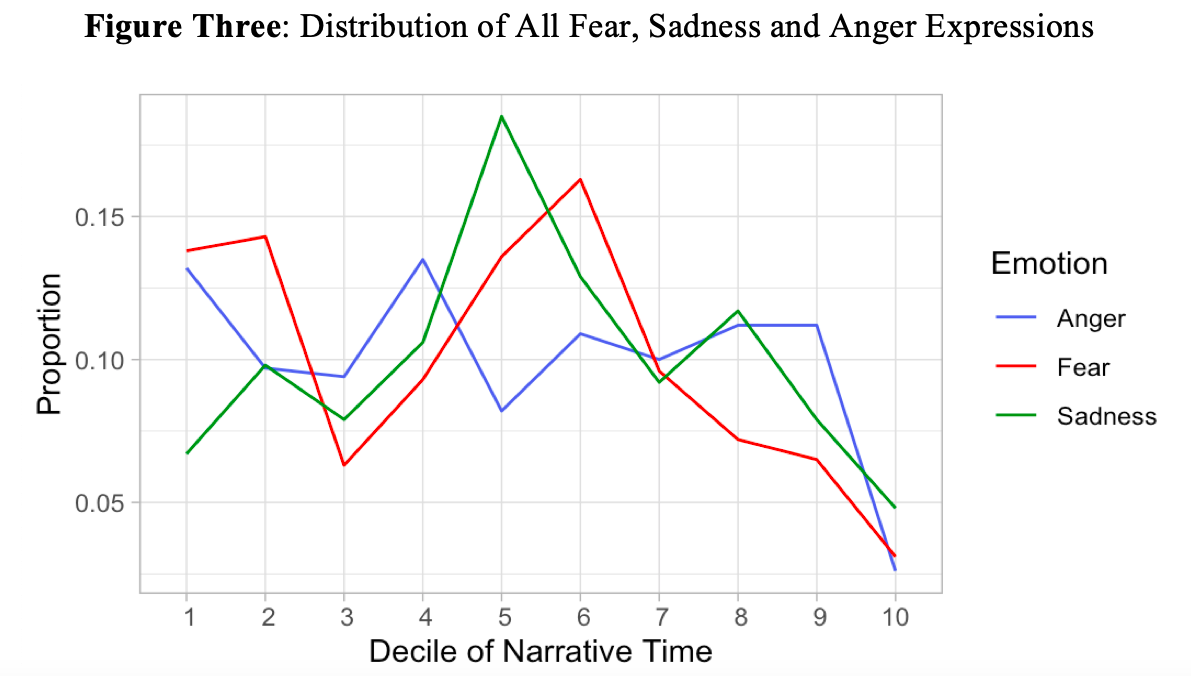

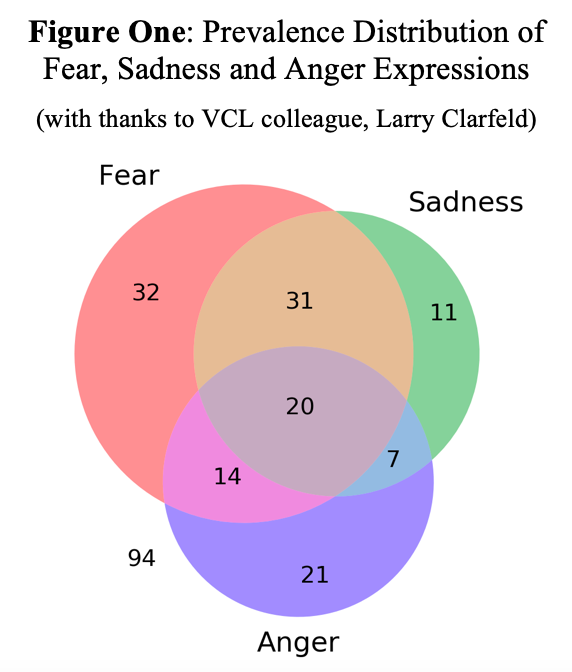

As shown in Figure One, 59% of conversations contained at least at least one expression of fear, sadness or anger (136/230) and 31% included multiple types (72/230). Fear demonstrated the highest prevalence (42% of conversations; 97/230) followed by sadness (30%; 69/230) and anger (27%; 62/230). As shown in Figure Two, when fear and anger are expressed in a conversation, they both most commonly emerged at the very beginning of the conversation (decile 1). When sadness was present, the most common first expression happened in the middle third of the conversation (decile 4).

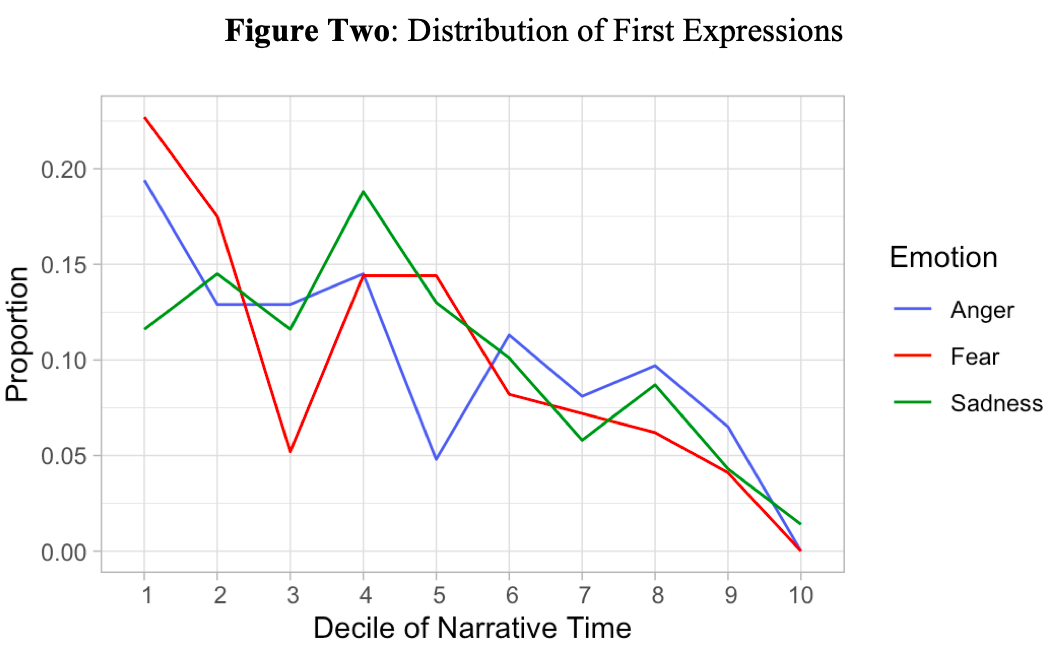

Fear was the most frequently expressed of the three distressing emotions (572 turns) followed by sadness (480 turns) and anger (340 turns). All three peaked in their frequency during the middle third of the conversation (Figure Three). Fear and anger demonstrated a relatively pronounced bimodal distribution in peak frequency with the second peak happening in the first decile of the conversation.

So, what does this all mean? First, our findings support previous work demonstrating the high prevalence of distressing emotion in palliative care consultations (Alexander et. al., Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2015) Second, we also observe similarities to this previous work in both prevalence and frequency of fear (highest), sadness and anger (lowest). Third, we observe that a majority of conversations demonstrating one type of distressing emotion will also contain another type. Fourth, we observe a pattern in the timing and distribution of emotion expression over narrative time suggesting that fear, sadness and anger may represent different types of conversation arcs.

We conclude that multi-dimensional expression of distressing emotion is endemic to palliative care consultations and that fear, sadness and anger may hold distinct roles in the unfolding shared narrative. More research is necessary to inform whether expressions of fear, sadness and anger cluster into different fundamental types of conversations and, if so, whether those types have differing clinical trajectories or implications for achieving high quality care in serious illness.