15. Can Identifying Conversational “Hot Spots” Reduce The Computational Footprint Needed to Analyze Big Communication Data?

| Author: Zac Pollack, Bob Gramling Project: SOCKS Conversation Analytics October 2024 |  |

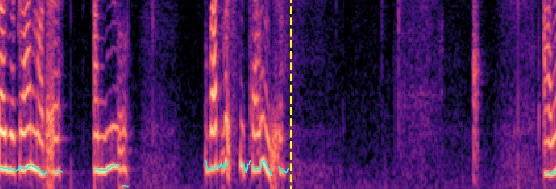

14. Expression of Awe in Psilocybin Assisted Therapy

| Author: Ian Bhatia, Tej Thambi Project: Psychedelic Assisted Therapy |  |

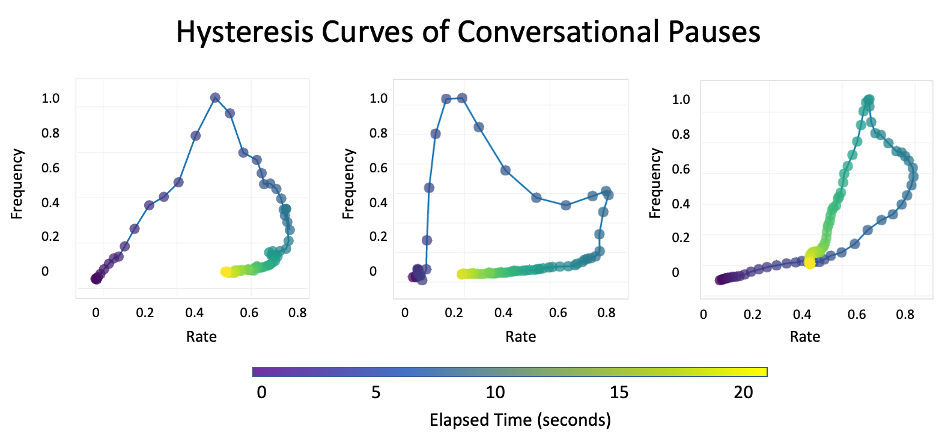

13. Hysteresis Curves to Visualize Patterns in Conversational Time Series Data

| Author: Advik Dewoolkar, Jeremy Matt & Donna Rizzo Project: The StoryListening Project |  |

12. Lexicon of Loneliness

| Authors: Hope Linge, Elise Tarbi and Maija Reblin Project: The StoryListening Study |

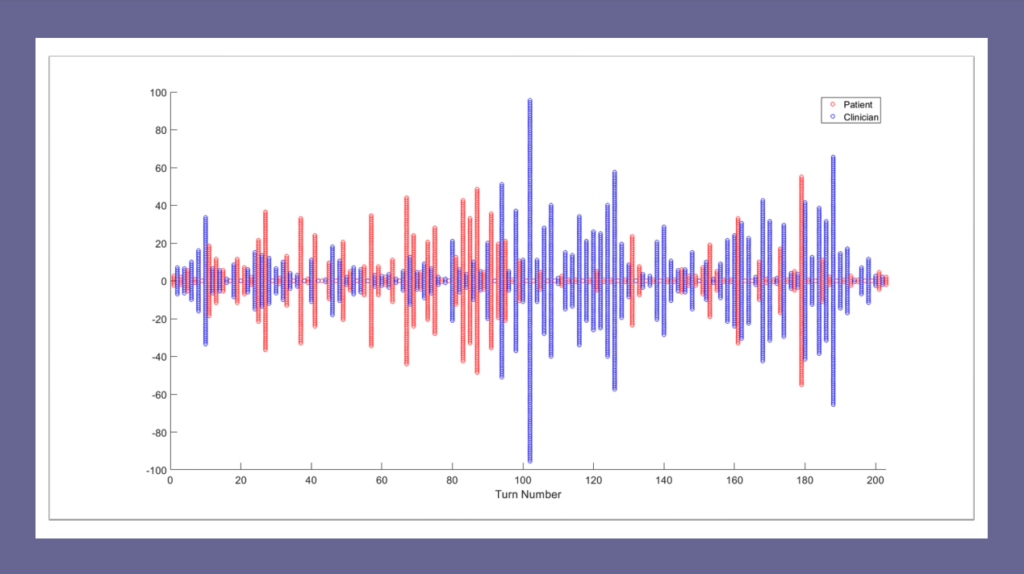

11. “Zipper Plots” of Conversational Information Flow

| Author: Larry Clarfeld Project: Palliative Care Communication Research Initiative |  |

10. StoryListening Study Doula Reflections

| Author: Matilda Garrido and Greg Brown Project: StoryListening Study |

Matilda and Greg are graduates of the University of Vermont End-of-life Doula Professional Certificate Program. They have been StoryListening Doulas within The Conversation Lab’s StoryListening Project—a brief conversational intervention designed to reduce the existential loneliness of grief during the social distancing of COVID. In this blog, they will share some experiences and lessons learned through their participation.

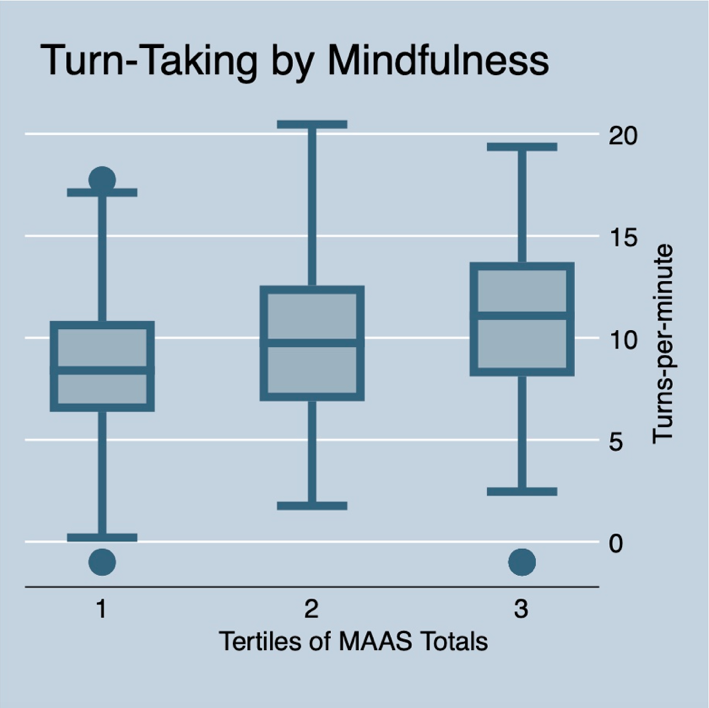

9. Mindfulness & Conversational Turn-Taking

| Author: Robert Gramling Project: Palliative Care Communication Research Initiative |  |

Mindfulness is “awareness that arises through paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgmentally.” Efforts to promote mindfulness in healthcare result in physicians feeling more curious about their patients’ experience. When seriously ill patients feel this non-judgmental curiosity from their clinicians, they are likely to more fully engage in conversation and, ultimately, share more about what matters most to them in their medical context. Very little, however, is empirically known about the relation between clinician mindfulness and actual features of healthcare conversations with seriously ill people. Here, we evaluate the degree to which clinician self-ratings of mindfulness (i.e., Trait Mindfulness) is associated with key conversational dynamics of engagement.

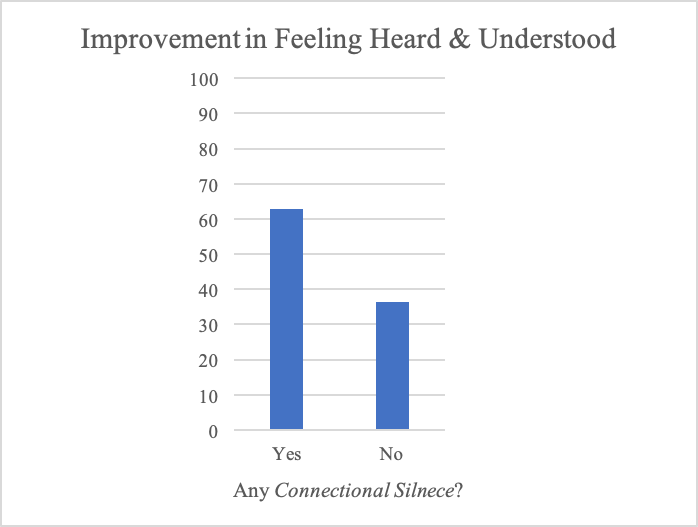

8. Is silence a predictor of better communication outcomes?

| Authors: Cailin Gramling & Robert Gramling Project: Palliative Care Communication Research Initiative |  |

Within serious illness conversation, the feature of silence can act as a communicative and data rich moment. As established in our previously published paper (Durieux et al. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2018), some types of pauses represent moments of human connection.

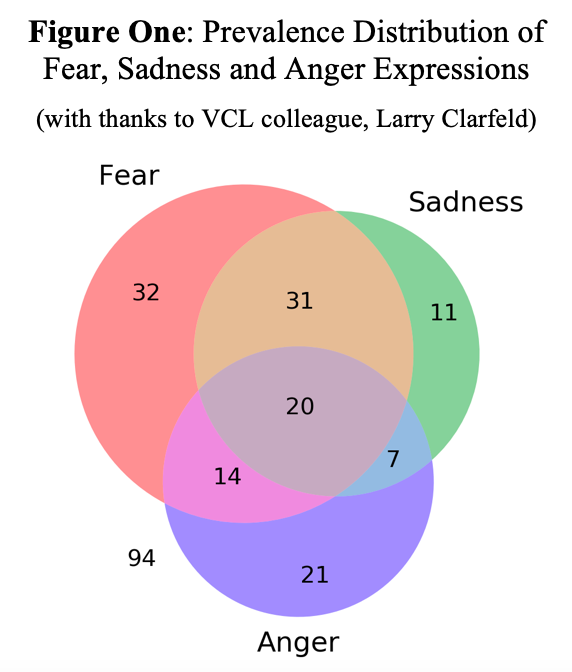

7. Timing of Fear, Sadness and Anger Expression in Palliative Care Consultations

| Authors: Jack Straton & Robert Gramling Project: Palliative Care Communication Research Initiative |  |

Fear, sadness and anger are commonly expressed during palliative care consultations (Alexander SC et. al. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2015). Recently, we discovered that features of serious illness conversations organize into observable arcs in the shared narrative (Ross LA et. al. Patient, Education and Counseling. 2020).

Little, however, is known about the typical trajectory of fear, sadness and anger expression in these conversational stories and whether these arcs differ by the type of emotion. Better empirical understanding of the epidemiology of serious illness conversations is essential to guide effective quality measurement, system re-design, and communication training.

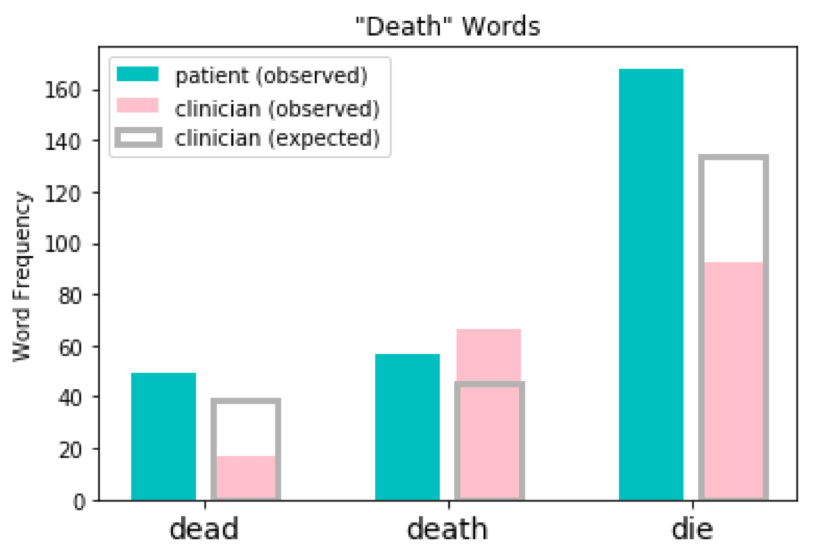

6. Word Prevalence: “Patient” vs. “Clinician”

| Author: Larry Clarfeld Project: Palliative Care Communication Research Initiative |  |

“Words are chameleons, which reflect the color of their environment.”

Something so simple as which words we choose to speak can be as nuanced and complex as any other aspect of human conversation. As the above quote from the influential American judge Billings Learned Hand suggests, the people with whom we converse can have a significant impact on what we say and how we say it.

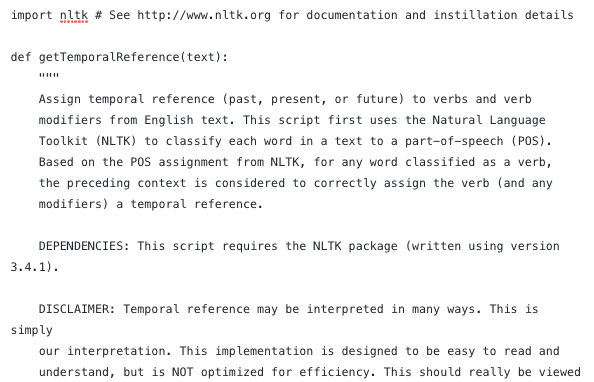

5. The VCL Temporal Reference Tagger

| Author: Larry Clarfeld Project: Palliative Care Communication Research Initiative |  |

“Have you decided to read this blog?”

Is this sentence referring to the past tense? The present? The future? All three? There is no universally accepted methodology for assigning temporal reference to text or speech, however when VCL alumnus Lindsay Ross wanted to investigate how temporal reference evolves in palliative care conversations, she was surprised to find there were no publicly available resources for accomplishing the task. So, she created one.

In this blog post, we share the methodology behind the ‘VCL temporal reference tagger’ (TRT) and provide source code in Python for anyone wishing to use this tool in their own research endeavors.

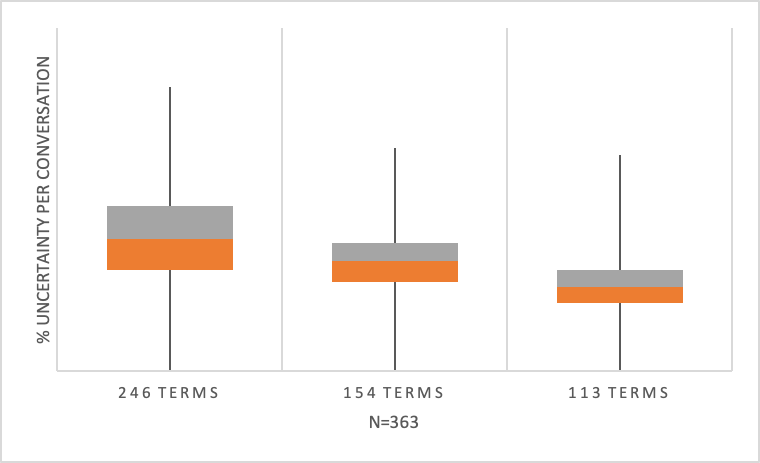

4. Uncertainty Corpus

| Author: Brigitte Durieux Project: Palliative Care Communication Research Initiative |  |

As do any variables, language measures require conceptual framework; one must be able to recognize or mark something to quantify it.

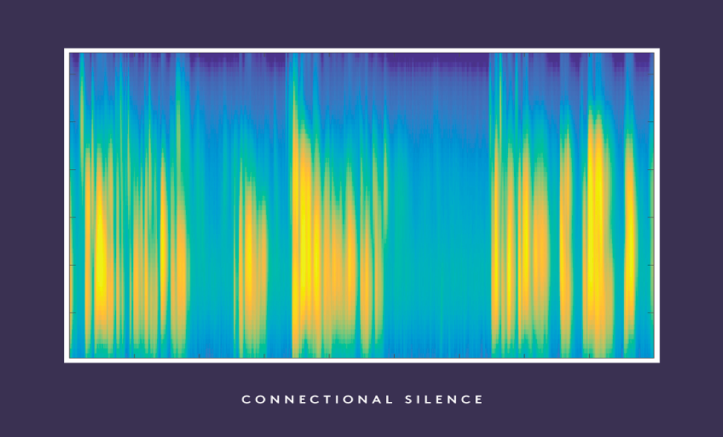

3. A Case Study of Conversation Surrounding a Compassionate Silence

| Author: Cailin Gramling Project: Palliative Care Communication Research Initiative |  |

A compassionate silence is defined as: “A 2+ second pause in speaking that follows a moment of gravity…in which the person who speaks immediately following the pause acknowledges the gravity of that moment or makes a statement that offers to continue the expression of emotion (e.g., ‘‘It’s a lot to take in, isn’t it?,’’ ‘‘Can you tell me more?’’).

In order to fully understand an episode of such a silence, it needs to be examined within its surrounding environment.

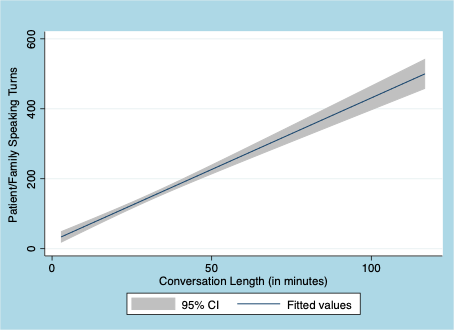

2. The Value of Time

| Author: Robert Gramling Project: Palliative Care Communication Research Initiative |  |

As our science of palliative medicine grows, it is safe to put our empirical nickel down on two things.

1. Responding to Gravity

| Author: Brigitte Durieux Project: Palliative Care Communication Research Initiative |  |

Understandably, the end-of-life setting can be an emotional and heavy one. First and foremost, those affected are the people experiencing the end of their lives – but there also exists an emotional toll on clinicians and researchers within palliative care.